A wealthy car dealer’s wife disappears

‘Auto Motive,’ Forensic Files

While the world was watching news of the terror attacks on Manhattan’s twin towers, a smaller-scale tragedy was playing out in rural Tioga County, New York.

Michele Harris, a 35-year-old mother of four with a rich husband, never came home after her waitressing shift on September 11, 2001. With local police helping out at the World Trade Center site, they couldn’t devote much time to an investigation right away.

And once they opened the case, their efforts to find a body or a murder weapon yielded nothing. They would have to wait years to go to trial, with only scant forensic and circumstantial evidence.

Funds equal freedom. The episode, produced in 2011, left some questions. As Forensic Files noted, despite that Michele and Calvin “Cal” Harris were getting divorced, she lived in the family home to prevent his side from making charges of child abandonment. But why was Michele working as a waitress when Cal’s car dealerships were so profitable?

And a bigger question: What is Cal’s incarceration status today? He was convicted in 2007, but murderers with resources often pole-vault their way out of prison early (Suzy Mowbray, Michael Peterson, Glen Wolsieffer).

So let’s get going on the recap of “Auto-Motive” along with extra information from online research.

Estate owners. Michele Anne Taylor grew up in Spencer, New York, and got an associate’s degree in business from SUNY Morrisville. She was petite with blond hair, brown eyes, and a beautiful smile.

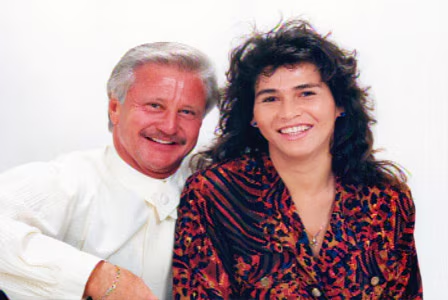

Calvin “Cal” Harris was a former high school lacrosse star who eventually took over the auto-sales empire started by his father. He and Michele met while she was working as a secretary at one of the dealerships. They were both in their 20s, with Cal a couple of years older. He already had thinning hair, but he was tall and slim with big blue eyes that probably charmed Michele.

The two married in 1990 and soon began living large. They built a house to their specifications on 250 acres. Michele and Cal had all-terrain vehicles, a canoe, and a larger boat.

Flitting toward a love nest. The Harrises had a nice social life together, often spending time with Thomas and Cindy Turner, who were originally Michele’s friends. As a teenager, she had babysat the Turners’s kids, and she stayed close to the couple throughout her adulthood.

At some point, or possibly at many points, Michele found out that Cal was cheating on her. He once took a girlfriend to Daytona Beach, Florida. In 2000, Michele began sleeping on the couch. Still, when she first told Cal she wanted a divorce, he refused. She filed in January 2001.

Michele needed spending money, and Cal apparently wasn’t sharing his wealth. She and 23-year-old boyfriend Brian Early, a Philadelphia land surveyor, were both raising funds to buy a home to share. Michele planned to sell her jewelry.

One after another and another. But why did she choose waitressing as an occupation — and not at a country club but rather at Lefty’s, a rollicking joint patronized by some rough customers?

Cal would later acknowledge that it had been hard for Michele to have so many pregnancies so close together. Their two sons and two daughters were all under the age of 8. My guess is that, for Michele, Lefty’s was a little escape from her demanding home life and the unfun mechanics of dissolving her marriage. And it probably made her feel young again. She liked going out with colleagues for a drink or two after her shift.

But she had never stayed out all night until September 11, 2001.

Casting a dragnet. When Michele’s 2000 Ford Windstar minivan turned up empty with the keys in the ignition at the end of her and Cal’s driveway, the family called authorities. Her cell phone was in the vehicle and she hadn’t answered it all day.

On September 12, she didn’t show up for an appointment with her divorce lawyer.

Once police could turn their attention away from 9/11, they went full force on Michele’s disappearance. The authorities dispatched dogs, human divers, and helicopters to search for her.

Co-worker’s secret past. Early on, investigators zeroed in on two suspects. Michele’s colleagues remembered that when she left the restaurant around 9 p.m. on September 11, she walked to the parking lot with Michael Hakes, a cook. His girlfriend provided only a partial alibi for him, acknowledging that there was an unaccounted-for 30 minutes between the time he left the restaurant and showed up at her house.

And Michael Hakes had a past hitherto unknown to his colleagues; he had served prison time for rape and attempted murder.

Then there was Michele’s boyfriend, whom Michele had seen on the night she disappeared. He said they parted at 11 p.m. On the driver’s side door of her vehicle, police found his fingerprints. Brian said he placed his hand there when he kissed Michele goodnight through the window.

In-depth accounting. But Brian, who told police he wanted to marry Michele, and Michael both passed polygraph exams. And neither of them had motives for murdering Michele.

Cal Harris had millions of them. Michele had rejected his offer of $750,000 to $800,000 to be paid out over 10 years after the divorce, and her side was forcing him to spend $30,000 for a full accounting of his assets.

Divorce records gave Cal’s net worth at $5.4 million, according to the Binghamton Press and Sun-Bulletin. And he wanted to stay in the house. Michele had asked a judge to remove him from it.

Cal refused to take a police-administered lie detector test.

‘You little hick.’ Investigators found out that Cal didn’t like giving up control over Michele. And he demeaned her to her face, according to the couple’s nanny-housekeeper.

“Cal had told her that she was born in Tioga Center, raised in Tioga Center, and she’d die in Tioga Center. Like, ‘You’re small town. You’re beneath me. You’re never going to be up to my level,'” Barbara Thayer told 48 Hours Mystery: A Time to Kill.

And the forensics were starting to look promising. Despite someone’s attempt to wash it away, Michele’s blood splatter turned up in the kitchen, hallway, and garage of the house — evidence that someone had beaten her.

Close friends not informed. When Cal heard that police had found what might be a body on the Harris property, he reportedly said that was impossible, suggesting that he knew Michele’s remains were somewhere else. (It’s not clear whether there really was a body on the property.)

It came out in court that Cal had driven past the Turners when they were taking a walk on September 12, and he didn’t stop to tell them Michele was missing or ask if they knew her whereabouts. The Turners only found out about her disappearance in the newspaper.

As for Cal, he was having no trouble getting on with this life. He put Michele’s van and clothes up for sale and continued to see his girlfriend, inviting her to the house. He allegedly told her not to worry that Michele might come home; she was gone for good. And Cal started in on typical smear-the-victim tactics (Jack Boyle) pretty much right away. He claimed that Michele “was no good” and used drugs and drank alcohol to excess. Cal told his in-laws that Michele kept a dirty house and that’s why he cheated on her, according to subsequent testimony from Gary Taylor, Michele’s father.

Staged scene. Authorities arrested Cal, but it took them years to build a case because they lacked a body or a murder weapon. In the meantime, they let Cal go free. Michele’s father, Gary Taylor, said he noticed that Cal could no longer look him in the eye.

When prosecutors finally put Cal on trial in 2007, they alleged that Cal beat Michele to death at the house, placed her in a plastic bag, carried it away somehow (no blood was found in Cal’s Ford 150 pickup truck), and buried her at an unknown location. Next, he drove her vehicle to the end of the driveway to make it look as though she either met someone or was abducted there. Cal couldn’t afford to abandon the vehicle far away from the property for fear of witnesses seeing him walking back.

Next, investigators believe, Cal tried to clean up the blood. Michele’s phone records proved that Cal hadn’t called her to ask where she was on September 11 or 12.

Cal testified in his own defense during the trial. He said that all of the witnesses for the prosecution were liars.

Satisfaction for Dad. The jury disagreed and convicted Cal of second-degree murder. Upon hearing the verdict, Cal wept, cried out “no no no,” and clutched a photo of his kids.

Michele’s relatives weren’t feeling too sympathetic toward Cal. According to the Binghamton Press and Sun-Bulletin:

“Two courtroom rows behind Harris, Gary Taylor — Michele Harris’ father — had his arms folded on his chest, his face expressionless, as he watched Harris disintegrate. ‘Arrogant bastard,’ said Taylor in a quiet voice. ‘Thought his rich daddy was going to buy his way out of this one.‘”

Slammer city. Jurors would later tell 48 Hours they voted guilty in part because of the blood evidence and the fact that Cal didn’t join the search effort when Michele disappeared.

Cal received 25 years to life and served at least part of his sentence in the Auburn Correctional Facility.

But as mentioned regarding killers, where there is money, there is hope. Over the years, he won the right to three more trials and a change of venue, to Schoharie County.

More to the story. Today, he’s out of prison — but is still making headlines and not for particularly wonderful reasons.

For the next post, I’ll look into Cal’s years-long legal maneuvering, how his children feel about him, and what he has percolating today.

That’s all for this post. Until next time, cheers. — RR

Watch the Forensic Files episode on YouTube